ArtLabo Retreat: a journey to the end of the world

Published 25 July 2025 by Lyndsey Walsh

From the 30th of June until the 6th of July, the third ArtLabo Retreat took place on Île de Batz, Finistère, France, inviting artists, designers, scientists, and students to explore the unique landscapes of the island and experiment with possible materialities of coastal ecosystems. Co-organised in Batz with La Gare, Centre d’Art et de Design, this retreat extended in the context of Fluxon at Kerminy castle, a sound art oriented week residency and one-day event on July 12 hosted by the association n-Kerminy. Artist and researcher Lyndsey Walsh reports on their journey, exploring the many facets of coastal landscapes and communities.

The journey to the end of the world didn’t take as long as I expected it to. After a six-hour drive from Paris and a short ferry ride from the Port of Roscoff, we arrived on the shores of Île de Batz, a small island off the coast of Finistère, the most western “département” of Brittany and France. While sitting out on the roof of Colonie du Phare, the hosting site of the ArtLabo Retreat, it was easy to see why Finistère is called following the latin “Finis Terrae” or “the end of the world”.

The wide and almost borderless expanse of the Celtic Sea stretched out endlessly into the Atlantic Ocean, which continued toward the horizon without any glimpse of land in sight. As the sun set and the evening mist rolled in, the mysterious nature of Batz as an island seemingly caught falling off the edge of this world’s end sank in. As much as I squinted, I could not see past the watery expanse, even though I knew that there was, in fact, more to be found beyond the horizon, as my own birthplace lay somewhere beyond it. This was only the end of Europe, but still, there was a weight of finality in that thought alone.

The ArtLabo Retreat on Batz, organised by ART2M in partnership with La Gare, Centre d’art et de design from Relecq-Kerhuon, and this year with its new partners n-Kerminy, lieu d’agriculture en arts and Swiss Mechatronic Art Society (SGMK), held its third edition from the 30th of June until the 6th of July. Part of the Feral Labs Network and its Rewilding Cultures project, a cooperation co-funded by the European Union, the retreat brought together artists, designers, students, scientists, and more to explore the land and waters of Batz while charting and navigating the complexities and materialities of coastal landscapes. It also extended the horizon of its investigations through the Archipelago program, an international art&science cooperation with artists from Switzerland (SGMK) and Japan (Sonda Studio), supported by Pro Helvetia, the Swiss foundation for culture. On local level, La Gare was supported by the Région Bretagne (international cooperation program) and the Drac Bretagne.

Joining the retreat as an artistic researcher, I found myself staggering through the uneven terrain and dramatically shifting tides that both the realms of science and culture have spent centuries in negotiation about how we know and understand coastal territories.

Even though coasts are a globally ubiquitous ecological feature of our world and operate as the most important site for most major cities and settlements for all of humanity, coastal zones are unique in how different terrains of land and water interact to shape how both non-human and human life can unfold. These areas of the world are not only facing dramatic shifts due to ongoing ecological phenomena, such as tidal variations, weather events, salinity changes, and land erosion. They are also heavily impacted by human activities, and their status has the power to shape the continuance of human life and culture.

Coastal territories have borne witness to some of the most major events in planetary history. Notably, they served as the first footholds between land and water for life stumbled upon as it emerged from our planet’s primordial seas.

One of these organisms that made the bold pursuit to climb out from the depths of the sea and onto land is lichens. The evolutionary timeline of lichens has become a contentious topic of scientific debate in the last couple of decades. However, in 2019, a paper published by Matthew Nelson and colleagues asserted that the arrival of lichens on land does not predate vascular plants, yet other scientists assert that possibilities in the fossil record may suggest earlier transitions of their life onto land. While Nelson’s study remains the current consensus, it is not based on evidence of the presence of lichens in the fossil record but rather through the use of time-calibrated phylogenies, evolutionary lineage trees, created with molecular analysis of the DNA from both different fungal and algal species that make up the holobiont we know to be lichens (1).

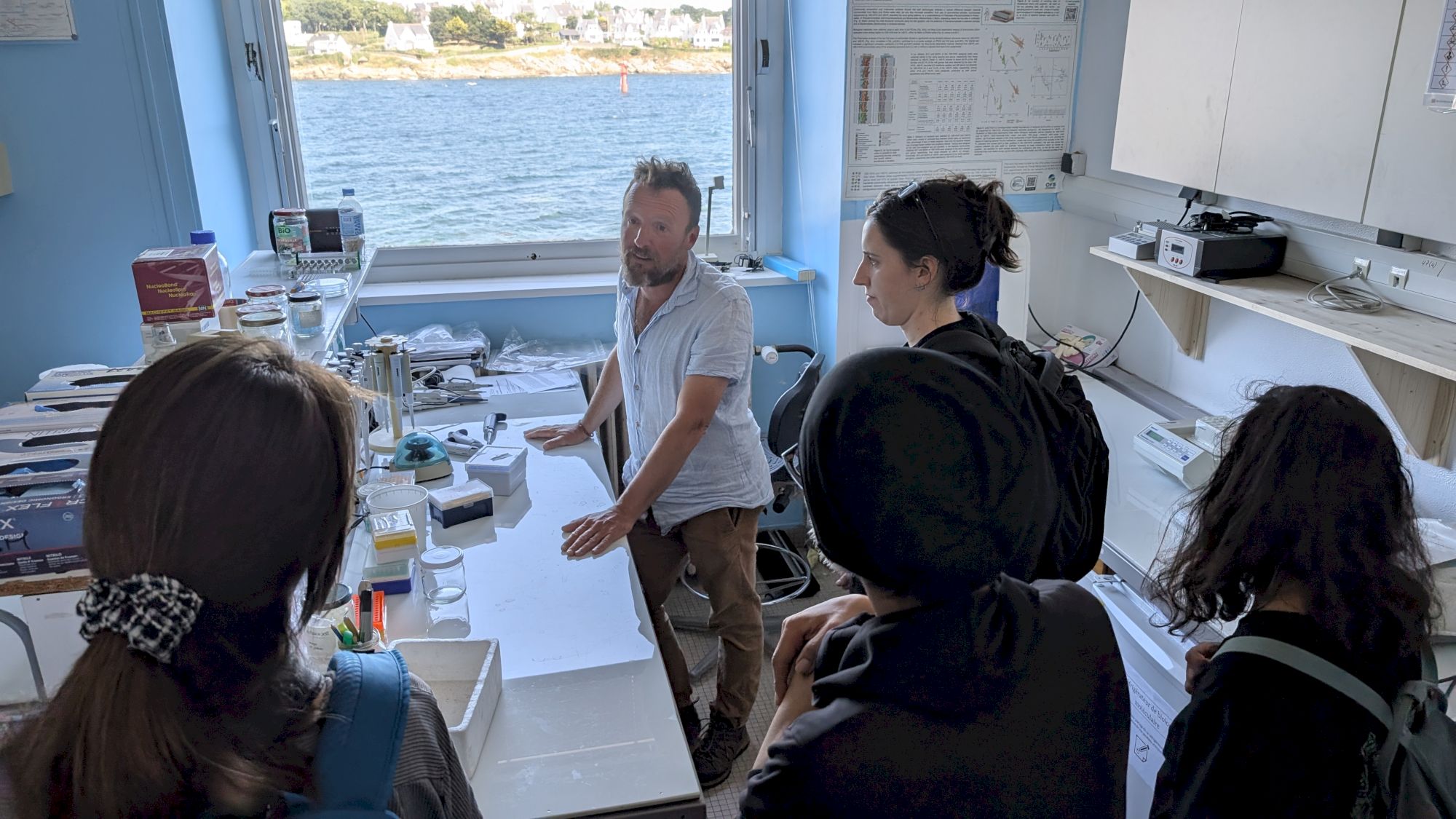

Scientist Dr. Tony Robinet, who is an Assistant Professor at the Concarneau marine station (Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle) and a participant in ArtLabo, has become fascinated by the origin story of lichens as a transitional point for life between the sea and land. He explained to me that the formation of the symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae allowed the algae to leave their watery homes with a new ability to survive in drought conditions under the protection of their fungal symbiont. The mysteries and complexities surrounding the origins of lichens on land are set to be the main subject of Dr. Robinet’s current film project with musician and sound artist Jean-Baptiste Masson, which they were producing in part during their time at ArtLabo Retreat.

While spending the day filming the local lichen coating everything on the island from the rocks to the trees and even the abandoned Corsaire’s House, previously used by privateers to keep a lookout over the island’s defenses, Tony translated the lively dynamics of lichen, pointing out how the depths of the tides can be read based on the types of lichen found on the rocks and the meaning behind different textures and patterns formed by the multitude of species co-existing on the island.

Serpent’s Hole

Ile de Batz is not only a site for unraveling the secret origins of the natural history of lichens, though. The island is also well known for its mythological battle occurring around the 6th Century between Saint Pol Aorelian, a Welsh vegetarian Bishop, and a dangerous sea serpent, whom Saint Pol cast out into the sea at what is now known as the Serpent’s Hole to make the island inhabitable for future residents. While this story remains a myth, it captured my attention as a potential artefact of culturally constructing information about the natural history of the island. Scholar Robert France notes that often in myths and folk tales that emerge from the sea, sea serpents represent possible real environmental threats or disasters that have taken place.

For ecological events that fail to leave a mark for science to investigate, these stories remain as small hints at wonderous possibilities for how earlier life could have been for both human and non-human inhabitants. The topic of these possibilities in light of other global cultural narratives that use monsters to facilitate knowledge on natural history and ecological traumas became the subject of my performance lecture hosted at our open day for ArtLabo on one of our last nights on Batz with a captivating re-enactment of the battle between Saint Pol and the sea serpent, featuring the retreat’s own vegetarian Welsh man, Steffan Jones-Hughes who is also the director of Oriel Davies Gallery and artist Gweni Llwyd, artist Corinna Mattner, and student Hanaé Laporte–Bruto who embodied the ferocious sea serpent by donning algae costumes made by Mattner.

Although locals see this as a metaphor for the eradication of Celtic paganism by Christianity, the myth of the sea serpent remains a mystery and finding ways to cooperate or form relations between different species is a key characteristic of sustaining coastal life. Brewer, doctor in cosmology, and local resident Tanguy Grall highlighted, during a talk and manifesto reading at the open day, the ways his micro-brewery PAB has been inspired by his pursuit into the science of fermentation as a way to, quoting philosopher Karen Barad, explore “intra-action with micro-organisms”, leading PAB to produce their beer by fermenting local wildflowers and other flora. For the people of Batz, the local flora has not been the only important feature of the island, as historically, seaweed also served as its main resource before 20th century. Many of the participants of ArtLabo found their own ways of working with seaweed, harvesting, processing it into textiles, cooking with it, and exploring other modes of material exploration.

Seaweeds are not only important historically for Ile de Batz, but they are a crucial organism in coastal ecosystems. Seaweeds play a vital role in food webs as primary producers due to their role as photosynthetic organisms that are widely consumed by other marine organisms. They are also key players in the development and health of coastal ecosystems, as they provide crucial habitat for many aquatic species, nurseries for juvenile organisms, sources of oxygen generation, and contribute to many human coastal activities, including food, pharmaceuticals, fertilizer, and animal feed (2).

From sea to land

As our time at Ile de Batz came to a close, a third of Batz participants moved inland to the castle of Kerminy, a private land housing an experimental market gardening micro-farm and autonomous artist residency combining transformative practices in agriculture with somatic sound experience. Park, the summer “parcours d’agriculture en art” is open for sound walks every Saturday during the season with artworks in the field of acoustic ecology and landart. The ArtLabo Retreat aimed for the first time to explore the theme of the earth in southern Finistère, working on sound art with the Kerminy residency and event Fluxon, as well as on watersheds and the relationship between the earth and the sea, with plans to visit the marine station in Concarneau and the rias of the Aven and Belon rivers. The impact of coastal worlding therefore remained present in our day-to-day explorations despite our shift in location.

While visiting the Concarneau Marine Station, we found shifts in the coastal landscape now on the southern side of Finistère. Nearby Concarneau lies the oyster farms of the Belon River Estuary, where its regional variety of flat oysters, known to be a delicacy of Brittany, grow alongside cultivated Japonica variety. These estuaries flow down the southern side of Brittany where they meet with the Atlantic Ocean. While in Concarneau, we met Dr. Samuel Iglesias, who shared insights from his research cataloguing and standardizing records of the diversity of cartilaginous fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean (3). While the biodiversity of the coastal ecosystem that we visited was abundant, Dr. Inglesias reminded us that most of the species in his study were greatly endangered or about to become extinct.

As humans depend heavily on coastal environments for accessing resources, shipping, ports, and more, the impacts of the anthropogenic effects of these activities on the environment also put coasts at risk due to anthropogenic pollutants, overfishing, poor coastal zone management, and more (4).

L’Appel du vide

These ongoing frictions between human and non-human capacities over these coastal territories served as the inspiration for a final performance titled “L’appel du vide” of “the call of the void” created by artist Maya Minder, artist Corinna Mattner, Sound artist Pom Bouvier-b, and myself. It was fitting for us that while we were residing at the “end of the world” in Brittany, we attempted to find a way to embrace “the call of the void”, which often refers to the desire to step into the unknown despite the risks at hand.

In the performance, we invited participants to attempt to wash away their human egos and selves using soap we crafted from our own harvested seaweeds. After the washing ritual, participants were offered to find ways to engage in multispecies perspectives of self-care facilitated by the consumption of kombu and wild herb teas and wearing algal face masks, while Bouvier-b held an improvised sound performance that was followed by a meditative guiding of the possible more-than-human unknowns led by Minder’s recorded voice.

The future of coastal ecosystems is yet to be determined. It may be silly to state that this journey to the end of the world has made it ever more clear to me that we are not yet at our world’s end. It is up to us to decide how we will act and offer our hands up to forge relations with the species we share these landscapes with. We must decide together how best we can move forward into the unknown.

ArtLabo Retreat is part of the Feral Labs Network and the Rewilding Cultures program.

Notes: