Sonic Waves: Insights from the 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference

The United Nations Ocean Conference 2025 took place from June 9 to 13 in Nice, France. The week leading up to the conference provided an opportunity to explore multiple scientific, artistic, and cultural perspectives on the role of sound in ocean environments. From the detrimental impact of anthropogenic noise on marine entities and ecosystems to the hopeful regenerative potentials of acoustic enrichment, the impact of sound captured the attention of world officials and conference attendees.

Lyndsey WalshFor oceanic entities, sound is one of the most crucial forms of energy. Unlike light, which barely penetrates the depths of our planet’s waters due to its rapid scattering and absorption, sound travels faster, farther, and clearer in marine environments. The acoustic ecology of our planet’s oceans is both a crucial indicator of its well-being and a fragile soundscape, highly vulnerable to external interference and noise.

During the 2025 United Nations Oceans Conference, taking place in Nice, France, the role of sound and noise in oceanic environments permeated not only scientific advocacy and collaborative world government priorities, but it also reverberated across the conferences designated Blue and Green Zone’s transdisciplinary programming and expanded out into the surrounding events and installations across Nice.

Marine noise pollution

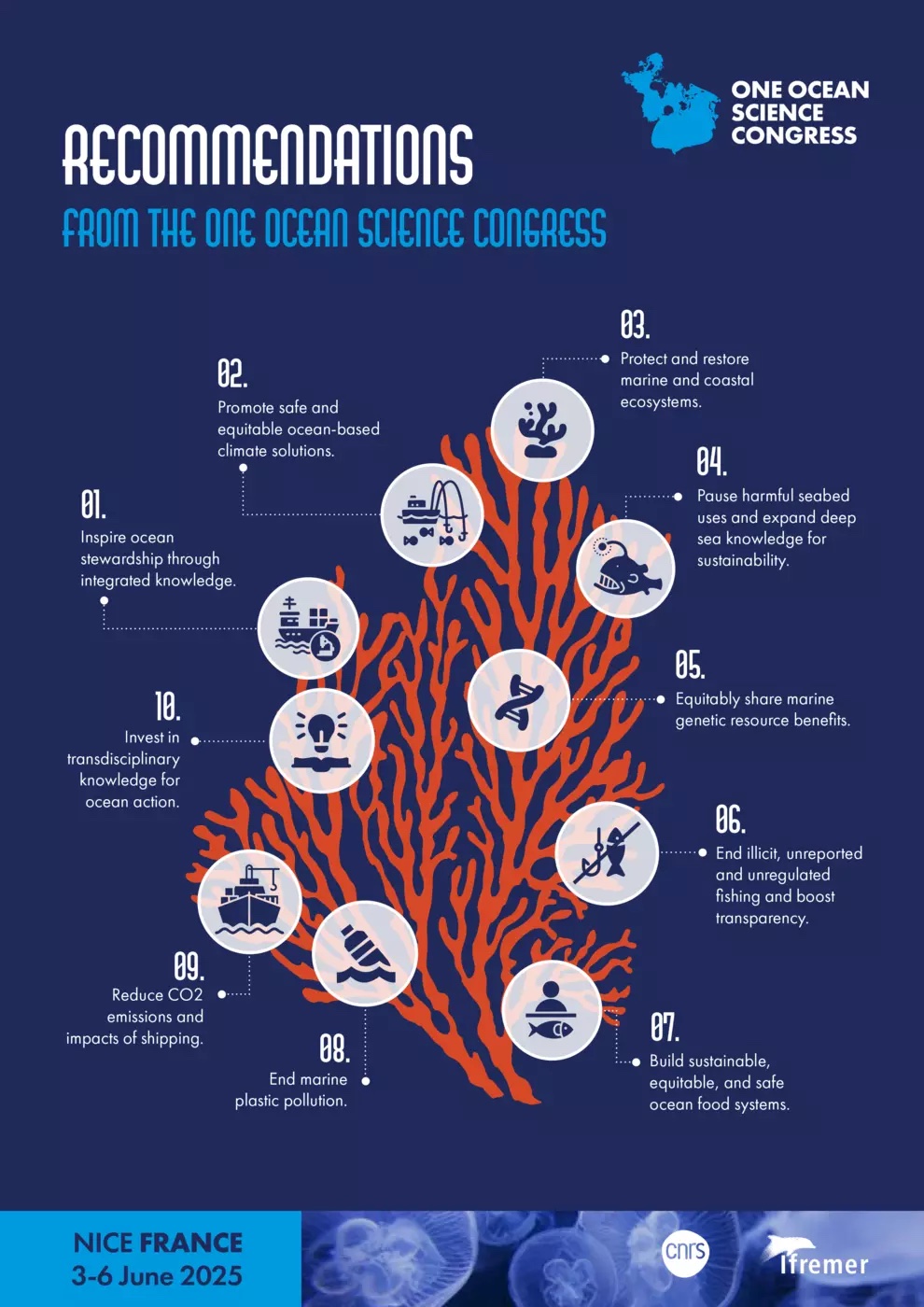

Preceding the official presentation of the UN Ocean Conference, on the 5th of June 2025, the One Ocean Science Congress presented their ten official recommendations, as announced by the event’s designated spokespeople including the French Institute for Ocean Science Ifremer’s President and CEO François Houllier, French National Centre for Scientific Research’s (CNRS) Research Director Jean Pierre Gattuso, Friends of the Coco Island Foundation (FAICO) Executive Director Alejandra Villalobos, Michelin-starred Chef Olivier Roellinger, and Professional Offshore Sailing Team Malizia’s Skipper Boris Herrmann. Alongside nine other recommendations drafted by the scientists of the One Ocean Science Congress, the spokespeople highlighted the “importance of decarbonizing shipping and reducing the environmental impact of maritime transport”, giving special attention to the need to identify Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas that are currently at risk noise pollution.

When thinking about anthropogenic impacts on our planet’s oceans, noise is not a commonly thought-of variable. The intangibility of noise makes it an ephermeral matter, often escaping the graphic grab for public attention that other forms of oceanic pollution have in public consciousness. However, if we were to take a moment to listen to our waterscapes, it would be easy to discern how loud our oceans have become.

Interspecies dwelling

Listening is what S+T+ARTSWater II Challenge and Residency artist Stijn Demeulenaere does best. Leading with an artistic practice set on trying “to understand places by listening to them”, Demeulenaere’s current project “Saltvein” ventures out into the seabeds of the North Sea surrounding the port of Ostend, located in the Flemish region of Belgium. “Saltvein” listens closely in on the local shellfish reefs of the area, finding the ways that emerging and shifting policy-making, fisheries, climate change, and military efforts characterize and are transforming the composition of sounds and ways of living for human and non-human entities in the Northeast passage of the North Sea.

While in Nice, Demeulenaere gave a performance of his work “Sounding Lines” at Villa Arson as part of the Symposium and Live Program “POROUS — Ports as Interspecies Dwelling” curated by Maria Montero Sierra of TBA21-Academy on June 7 and 8 as a S+T+ARTS4Water side event of the “Becoming Ocean” exhibition by Tara Ocean and TBA21-Academy. During his performance we could begin to hear from the many sounds he has been collecting during his residency hosted by GLUON-Platform for Art Science and Technology in Brussels.

“POROUS” two-day program, taking place on World Ocean Day and coinciding not only with UNOC but also Biennale des Arts et de l’Océan 2025, also featured another S+T+ARTSWater II Challenge and Residency artist named Carlos Casas. In the context of the S+T+ARTS Water II Challenge, Casas is bringing to the surface an auditory map of the city of Venice’s Lagoon by exploring a speculative narrative about its origin in his project “Allied Governance. From the Venice Lagoon and Its Citizens to the Ports” in his residency hosted by TBA21-Academy in Venice. For “POROUS”, Casas presented his performance entitled “LACUNAE”, which shared some of his explorations of the Lagoon’s soundscape that transforms across the layers of the Lagoon, as the artist leads us down a descent into its unexplored benthic zones.

While port zones may share the common feature of being particularly frictional sites between humans and non-humans when it comes to sound and noise, the impact of anthropogenic noise extends beyond these complex intersects in meeting areas between terrestrial and marine entities. During the One Ocean Science Congress, the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) held a screening of the Emmy award-winning documentary “Sonic Sea” at La Baleine.

Coalition for a Quiet Ocean

Tracing the catastrophe of mass whale beaching events, “Sonic Sea” reveals how whales are indicators of the current crisis our planet’s oceans are facing due to the increasingly destructive noise coming from shipping, military, and industrial activities. One of the major forms of sound pollution discussed in the documentary comes from what is called cavitation, which is the formation and collapse of air bubbles in the water due to changes in pressure changes. Cavitation not only causes disturbing amounts of noise in marine environments, but because it can occur around ships’ propellers, it also can actually lead to considerable damage to the vessels themselves.

Sonic Sea, trailer:

However, in the ocean, these forming and collapsing bubbles can send shockwaves that sonically reverberate at immense volumes and speeds. Increases in the speeds of vessels and the number of ships being used for shipping can lead to increasing noise pollution from cavitation. However, improving propeller design can not only alleviate cavitation, but it can also improve shipping efficiency and sustainability.

Other sources of problematic noise come from the use of sonar, as it can overwhelm marine mammals like whales who use their own sonar to communicate with their hunting, family, and social groups. In some cases, the noise of sonar can lead to loss of hearing and eventual mass beachings. These mass beachings are not only a problematic behavioral phenomenon, but the film “Sonic Sea” explains how often times, the whales beached also present with physiological symptoms from the impact of this harsh noise in the form of gas bubble lesions, which present in their tissues in a similar manner to that of Decompression Sickness found in divers.

IFAW explains that there is no existing global or local regulation for sound or sound pollution in marine environments, leaving vessels with no operating standards for the amount of noise that they can emit into open waters. The outstanding issues concerning noise garnered the attention of not only the One Oceans Science Congress preceding the UN Oceans Conference, but they also received active addressal in the UNOC’s “Nice Ocean Action Plan”. Under the leadership of Panama and Canada, the “High Ambition Coalition for a Quiet Ocean” coalition composed of 37 countries was launched. The signed declaration of the coalition pledged to develop a new policy for quieter ships, investigate and implement solutions toward a reduction of shipping and other maritime vessels impact on marine organisms, knowledge-sharing of tools and technology for ocean noise reduction, and further establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPA) with the goal of restoring and preserving the ocean’s soundscape.

Songs of corals

While our oceans may be at high risk for noise, sound also has been found to play other crucial roles in ecosystem management. Acoustic Ecology represents the field of study of the environment through its soundscape. Artist Marco Barotti, working alongside acoustic ecologist Dr. Timothy Lamont, has built up his project “Coral Sonic Resilience” by looking at the potential of what is called acoustic enrichment to save coral reefs. Unlike noise pollution, acoustic enrichment is the process of using soundscapes of healthy environmental areas to bring enhanced or restorative effects to a local ecosystem.

Barotti’s “Coral Sonic Resilience” plays the soundscape of a healthy coral reef to vulnerable corals in the hope of restoring the ecosystem back to a healthy state. The work submerges 3D-printed sculptures designed from scans of bleached corals that act as solar-powered speakers playing regenerative soundscapes of healthy coral reefs to attract new life back to degraded coral reef habitats. Listen to a Coral Sonic Resilience’s excerpt here.

Barotti first began his work looking at corals during his residency with Science Gallery Berlin in his project “CORALS” where, in collaboration with researchers at the Bifold Institute in Berlin, he interpreted datasets of oceanic conditions through sound. Fueled by his exploration of shamanistic rituals and speculative research, Barotti became then inspired by what scientists like Dr. Lamont were doing by using sound to transform oceanic environments through promoting ecosystem regeneration of coral reefs.

The short film documenting “Coral Sonic Resilience” was screened in Nice at the Institut de la Mer of Villefranche-sur-Mer. Barotti’s work has also recently received the S+T+ARTS Prize 2025 Honorary Mention with jury comments highlighting and applauding the work’s creative solution toward the restoration of one of our planet’s most valuable ecosystems. Barotti was not the only advocate for coral health at UNOC, as the One Ocean Science Congress also emphasized its ongoing interest and recommendations toward ensuring the protection of coral reefs. Indonesia, in collaboration with the World Bank, also introduced the “Coral Bond” as an outcome-based financing structure for further financing of conservation initiatives in Marine Protected Areas.

Despite the harshness of noise that can be found reeking havoc our oceans, as seen at UNOC, there remains a committed drive toward facilitating not only quieter marine spaces but also promoting a hopeful regenerative approach to sound as a means to bring about new possibilities for ocean conservation and management.